Friends or Strangers: Who Is Backing Kickstarter Projects?

Kickstarter bills itself as an artistic utopia, a democratizing chunk of the world wide web where anyone can create a project and witness the merits of an idea translate into actual dollars. The site boasts that it is a platform “full of ambitious, innovative, and imaginative projects that are brought to life through the direct support of others.” The platform is idealistic, pushing that projects are evaluated exclusively on the merits of one’s idea in a Darwinist landscape free from the corruption of big business.

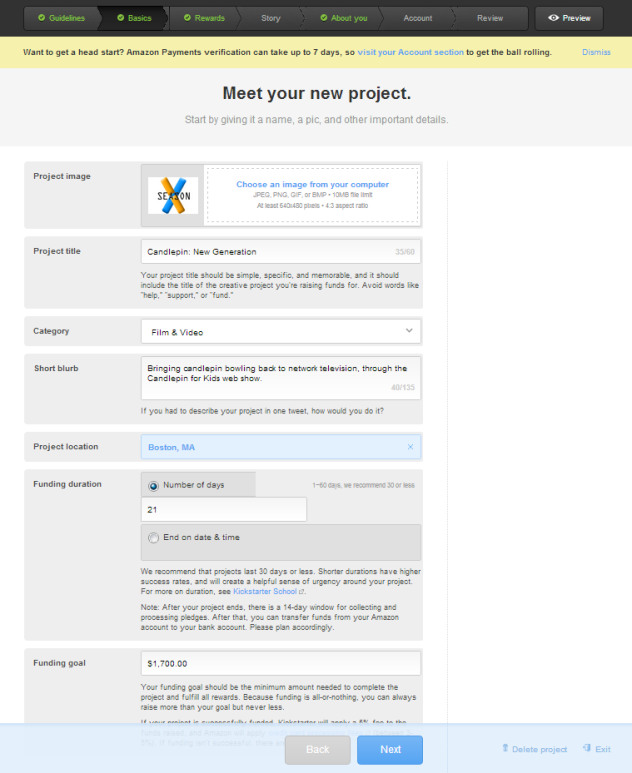

And at first blush it appears so, as creating a Kickstarter is simple. Any person with a project they’d like to get funded can go onto the website, submit their project idea, pretty it up with pictures, graphics and videos, and set a goal for how much he or she would like to raise. Like a gardener, the project-designer tenuously cares to their project, working to develop fans, get press coverage, and build momentum to reach their funding goal. Backers can pledge money to the cause in exchange for rewards that range from cyber-handshakes to direct involvement in the creation process. After an amount of time determined by the project creator elapses (typically around the thirty-day mark), time is up. If the project raised more funds than its goal, all backers are charged, the project is funded, and the creator has the opportunity to flex his or her creative muscle and bring the design to the world. If it does not, no backers are charged, and the project doesn’t get off the ground.

A look at the interface of designing a Kickstarter, through a sample project.

Kickstarter bills itself as democratizing, claiming that it “open[s] the door to a much wider variety of ideas and allow[s] everyone to decide what they wanted to see exist in the world.” The website places responsibility on project-backers to determine which projects merit taking the next step, and which ones don’t. A perception exists, which Kickstarter no doubt perpetuates, that there exists a benevolent community of backers that—assuming your idea is strong enough—can be tapped into. If your quality of idea is good enough, then you too could be one of the site’s success stories, independent projects raising six figures (sometimes seven, once even eight) to bring an idea to reality).

However, for small projects (a project category on Kickstarter, which is defined as a project looking to raise $1,000 or less), I was curious if that theoretical benevolent community really was a factor. A friend of mine was looking to raise $500 to help his band fund an album. I knew its existence because of Facebook—a message would scroll across my news feed daily from the friend, asking his social media community to head over to Kickstarter, take a look at his project, and drop him a few bucks. As he was only looking for $500, I wondered if it was possible for his Facebook friend community to do all the work for him, as he’d only need twenty-five friends to give twenty dollars. With one thousand Facebook friends, it certainly seemed in the realm of possibility. Especially when any person who donated twenty dollars received a copy of the album.

To research this phenomenon, I direct messaged fifteen active small projects on Kickstarter in diverse categories ranging from a band’s first album, to a table-top role-playing game about ants, to a carpentry video series. Each project, when first contacted, either had already been funded or was projected to be funded. Six responded, and I conducted email or phone interviews with each in order to learn the keys of success in each project, and to determine whether the “Kickstarter Benevolent Community” existed or not.

In my research, I unearthed several other variables which contributed to a project’s success. For some Facebook was integral, for others it didn’t play a part. Some of the founders cited their holding a micro-celebrity status within a community as a primary reason for being backed. Others were first-time project creators, who witnessed an unexpected amount of success. Some cited tactical manipulation of Kickstarter pages as reasons for their success, from writing style to creative prize structures.

As each project cited such drastically different reasons for success, I will go one by one through each of the cases to look at the reasons each founder attributed to his or her success. Of the six projects, half cited predominant support from the Kickstarter community, while half attributed success predominantly to their own built networks. We’ll start with the former.

Legend of Zelda: Hyrule University Shirt

Caleb Stultz’s project, a t-shirt honoring the video game “Legend of Zelda” with a custom-made graphic, is the best case of a Kickstarter success story. With a video that was nothing more than Caleb speaking to the camera with a video game score behind him, he raised over $1,500 to help produce t-shirts featuring his design in the first half of his thirty-day campaign, for which he set an initial goal of $1,000. Sixty-eight people have thus far backed his project, of which only eight he actually knows.

In a phone conversation I had with him, he noted that he was surprised not only the support he’s received, but also how far-reaching the project has become. Caleb noted several international orders which he didn’t initially account for in shipping costs, listing countries like Germany, France and Korea. Of his twenty-five single-shirt backers (meaning they contributed $25 each), fourteen were international.

In promotion, he lists his SoundCloud page on the Kickstarter site, directing people to other creative projects he’s undertaken. However, he noted that it may have been better if he listed his Twitter account first, as that is the only external media source he feels that has helped him out. By using targeted hash-tags, he was able to get a few followers who were fans of the Zelda series and fans of his work, which directly translated to pledge totals.

Finally, he cited Twitter’s own filtering system as a reason for his success. Upon being placed in the “Most Popular” category on Kickstarter, his campaign took off, netting him twenty-two backers in a weekend. The challenge, of course, is getting the initial momentum to be listed in the “Most Popular” category. This phenomenon is one that can be reconsidered in other cases.

Jack and Patrick Aubin had an even greater amount of success, raising over $5,000 for their rings made of carbon fiber, with an initial goal of only $500. Like Caleb’s t-shirts, the rings practically sold themselves on the platform. Jack noted that, “We assumed the same thing when we started, that we were going to have to go round up interest, but instead it seemed to just come right from Kickstarter.”

Despite some external coverage, the project didn’t receive any noticeable boosts from exposure. He noted “The only promotion we did was one posting on each of our Facebook walls when the project first started… We did have an external website but honestly I think only a handful of people have every visited that site.” Upon discussing assistance from people outside of Kickstarter, Jack noted the plug they received from German magazine “Mansgear” who found the product on the crowd-sourcing platform. The brothers were proud to promote it on their front page:

However, they noted no evident spike in sales upon getting the plug from the German magazine.

Jack estimated knowing fewer than 10% of his backers personally. Kickstarter’s analytics supported this claim, as 91% of backers came from within Kickstarter, and only 9% from external sources. Like Caleb, Kickstarter’s filters helped push people to the project, with over a quarter of the backing coming from the filters “recently launched” and “small projects.”

The final case funded by the perceived Kickstarter community belongs to Michael Desing, who created a role-playing game based upon a world of fighting ants which has raised nearly $2,600, with an initial goal of just $1,000, and eighteen days to go. The page is dynamic and loaded with content and updates ranging from the creator’s series of comics featuring the characters of his series. The video reveals nothing but a slide show of the artist’s work set to music, with a few simple title screens categorizing the project.

Like the two previously listed cases, Michael was surprised to see the support was coming from strangers: “I assumed that the primary (at least initial) support would come from friends/family, but I actually hit the goal before anyone I knew (except my mom) personally got involved. I’ve had a few friends/family pitch in, but at this point they are about 25% of the total support I’ve received.”

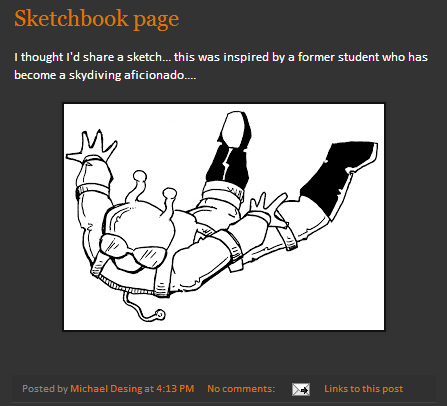

With just a simple personal Facebook page listed and a blog that updates viewers on the status of the project, the campaign has built a life of its own. The blog gives a reader insight into Michael’s personal life and musings, as he builds his own web personality through his updates, like this one:

Most importantly, however, is the online community which has jumped behind the project, with whom Michael conducts virtual relationships: “I’ve been incredibly pleased with the support I’ve received from the gaming community… none of whom I have personal contact with outside of forums/blogs. They are really an incredibly supportive bunch. They are really the key to the success of the project to this point.”

The micro-celebrity nature Michael has built up within the gaming community is only amplified in the next case study.

At first glance, Tim Carter is an anomaly on a platform full of gamers, musicians, and artists. Tim is a New Hampshire native whose Kickstarter bio lists a marriage of thirty-eight years, and a life as a “master carpenter, master plumber, and master roof cutter.” With a hand-held “selfie” video of under 0:45, a person jumping to conclusions may wonder how he even found Kickstarter in the first place.

Then, upon delving deeper, you learn that Tim is an internet veteran, with a website that achieves six-figure traffic called askthebuilder.com, which is plugged into every available social media outlet. However, he doesn’t attribute his success to the social media, noting:

I would like to add that I feel the social media promotional value of my three Kickstarter projects has been anemic. If I had to just rely on social media for the success of my projects, I feel NONE of them would have been successfully funded. I hate to say it, but I feel social media is not driving the bus when it comes to peeling money from people’s wallets and purses.

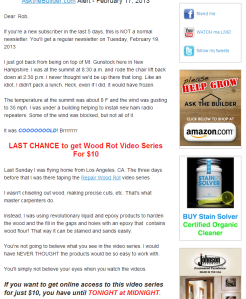

More important, however, is his weekly newsletter, with an audience that he’s cultivated over the past decade. Tim explains:

This is why my Kickstarter projects are being overfunded: I have tens of thousands of fans that *know* me because I’ve cultivated a personal and deep relationship with them over the years via my newsletter. Subscribe to it and study the writing and communications style I employ.

Upon subscribing myself to the newsletter, I witnessed a friendly writing style that combines personal anecdotes with plugs for his campaign.

A sample of Tim’s newsletter, featuring his reader-friendly writing style and personal requests to back his projects. Click to enlarge.

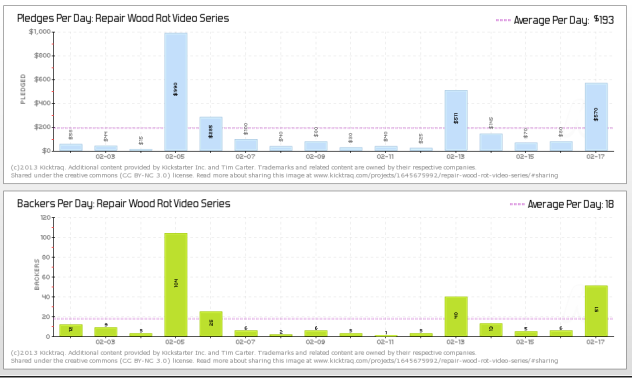

Sure enough, it was effective. Kicktraq.com, a site that provides analytics on Kickstarter projects, reveals three major spikes in Tim’s campaign, each of which corresponded with the release of an email newsletter:

Beyond his website and e-newsletter, Tim also cites that his reward structure, which gave people discounts for pledging early, was a possible factor in gaining early campaign momentum. He notes:

Not only did I create a radically different reward structure, but I also did NO promotions at all for the first four days. The only people that knew about my project were visitors to Kickstarter.com or anonymous people that signed up to be notified when I launch a project. I got quite a few people sign up organically this time in those first four days. I don’t know if it was the lower-priced rewards or if the Kickstarter community viewing the project were affected by wood rot at their homes and decided to discover how to repair it.

Smashy Claw, Full-Length Studio Album

Austin Aeschliman and his band, Smashy Claw, may not yet have Tim Carter’s vast web presence, but they’re working on it. A year ago, the band tried its first shot at Kickstarter, with a goal of $1,500 for its debut album. The campaign only received $221. Now, they tried again with a more modest goal of $300, and they passed it in the first few days. Now at $944 with eighteen days to go, the band looks like it may achieve the $1,500 goal it initially set. Austin attributes the lower target number as a primary factor for the success:

…it was about the tactics. For that first campaign, I set the initial goal amount as $1,500. That’s cause I wanted to record the whole album with the funds. The thing about Kickstarter is, you have to hit that initial goal you set or you get nothing. So I think we were doomed from the start at that point. Over a thousand dollars is quite a bit to ask for when you’re a little known alternative niche band on the internet. If I were even a fan of ours, I’d go to that page and think “Why even take the 30 seconds to pledge anything to this? It won’t succeed, and I won’t get anything.” The plan this year was to have that initial goal be $300. I think this allowed for people to be more comfortable about pledging to us, as it was more reasonable to assume they’d actually get a return out of the time put in (and future money devoted).”

As $10 will get a backer a digital copy of the songs and $15 a CD, Austin’s point shows that the Kickstarter community might not be an altruistic one, but rather people looking to gain something (as evidenced by only backing projects likely to succeed, rather than waste the time backing) and help the creative process as well.

Austin also referenced a similar phenomenon as Tim Carter’s micro-celebrity as a supporting factor. He states that “the bulk of pledges aren’t necessarily coming from an interested, altruistic community. It’s mostly from people I bring in through my incessant ads.” Just as Tim referenced the “one-way personal relationships” constructed by his newsletter, so too did Austin regarding his band’s building of a fan-base, saying “A lot of the pledges are from those people who I haven’t really met, but they consistently purchase my material, so I know the names.”

Never Give Up, Celebrating 10 Years of Postal Service

Finally, Stephen Carradini cited the usefulness of his Facebook page in driving pledges to his campaign. The manager of an indy-music and folk website, Stephen wanted to celebrate the tenth anniversary of his website and the tenth anniversary of the band Postal Service with his twenty favorite indy folk singers covering the album’s ten songs. Backers blew away his initial goal of $695 with $1,277 in commitments and eighteen days to go. Regarding Facebook, Stephen had a lot of praise:

I am very, very personally active on Facebook (not so much with my blog’s fan page, again because of the funneling policies that make being active there largely futile), so I have a large, active following that is interested in what I write. I had a ton of people who read a status, donated, then posted the link to donate on their Facebooks. This has even tipped me off that I have a new donation before my e-mail alert does, on occasion. (I get push notifications on my phone of when I am tagged in Facebook statuses.) This has been the primary driver of traffic: my people responding, and then my people posting it to their friend groups.

He further mentioned that every Facebook post he made correlated with a bump in backers. Regarding the possibility of a benevolent Kickstarter community, he said that he didn’t even need it (though he’ll certainly take it), and that the project would have still been funded even without people who found the page through Kickstarter. In addition, the project could have been funded if he only counted the contributions from people he knew. Although the project features a relatively project band, it was local support that got it funded, as he said, This project has been largely powered by my friends and family: no one but people I know have picked up the $100 option.

As they were the primary component of his success, he agreed to share the text of his Facebook post, all of which linked to the page through Facebook’s embedding feature, and not the actual URL:

The 10th birthday of Independent Clauses is here. To celebrate, I’m running a Kickstarter to finish funding a compilation album of my favorite bands. Please help me make a dream come true.

In a little over 24 hours, Independent Clauses’ Kickstarter is 40% funded at $282. Thank you all so, so much. I have been overwhelmed by all the support.

We’re funded after only 36 hours!!! I am absolutely blown away by the generosity of donors. Thank you all so, so much. (I then commented on my own status: “Now we can aim for the stretch goal of $250 extra and get a 6-week college radio campaign for the album! How cool would that be??”)

We blew away the stretch goal, so here’s a new one I’m calling SALLY FIELD MODE (famously misquoted as saying You Like Me! You Really Like Me!): $1250.

Conclusion

Every Kickstarter project, of course, is funded differently. The most common piece of each project’s success was its attention to detail and strategic manipulation of the page’s options. From Tim Carter’s discounts in prizes for buying early, to Austin Aeschliman’s reduction of the target goal, knowing how to properly manage a Kickstarter is a skill in itself. While traditional social media wasn’t a driving force in each case, every project (save carbon rings) was backed due to an ability to appeal to a community. The gaming community jumped behind Michael Desing, Facebook supported Stephen Carradini, and Tim Carter’s mailing list was happy to throw some money behind another video in a home repair series. Perhaps most important, each project showed a commitment to the campaign. All six campaign-founders updated their page at least once during the thirty days, often providing new incentives to backers and more ambitious goals for the project.

A final commonality that may have a factor on each project’s success was the responsiveness of the campaign-managers. Often, I heard from each within hours. And you know, I’m a pretty big fan of “Postal Service.”

mdeseriis 9:56 am on February 25, 2013 Permalink |

Rob, thank you for this thoughtful and very well-researched travelogue, I enjoyed reading it and learned from it. It is interesting that even though you chose a specific category of projects, there seems to be very little homogeneity among them so that your initial research question ultimately goes unanswered as each of them relies on a variety of preexisting social networks.

It also seems to me that Kickstarter plays an important role in promoting some projects over others so that the attention needs to be shifted, at least in part, from the role of strong and weak ties to the internal “protocological rules” of the funding platform. In this respect, the presentation video is key as well as the ability to attract donors within a short timespan. Once you have a funding strategy in place pledges can really come from anywhere. In this respect, I think that Kickstarter really says something epitomizes an emergent economic model that is shifting from large investments of physical capital in few selected projects to a society in which small, distributed projects have the potential of replacing the monopoly model of the (media) industries of the twentieth century. (Or at least this is Yochai Benkler’s argument on the funding model that should support the networked public sphere.)

Michael Desing 10:18 pm on February 26, 2013 Permalink |

This was a fun read! Thanks for sharing, and good work on this project. I hope you got a great grade!

Dave Przybyla 8:35 am on February 27, 2013 Permalink |

I’ve backed a dozen roleplaying Kickstarter projects, including that of Michael Desling. I have considered backing quite a few more. I’ve never watched the video for any of these. I’m a text guy and if you can’t compellingly explain your project to me in words I’m not interested. Of course, all the projects I’ve backed offer a book or PDF that’s full of words, so to me the writing ability is critical.

I just mention this to add another piece of data.